Northern Cyprus and Turkic unity: not conflict, but gradual progression

These days, the issue of Northern Cyprus is a hot topic in Turkey, Central Asia, and various foreign media outlets. Some claim that "Central Asia did not stay loyal to Turkic unity." So where do such claims come from, and who is spreading them? How did the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus come into being, and why are the UN resolutions about it being questioned?

The root of these discussions is related to the Samarkand Declaration, signed following the Central Asia–European Union Summit held on April 3–4. One of the declaration’s articles refers to UN Resolutions 541 and 550, adopted in 1983–1984. These resolutions emphasize the territorial unity of Cyprus.

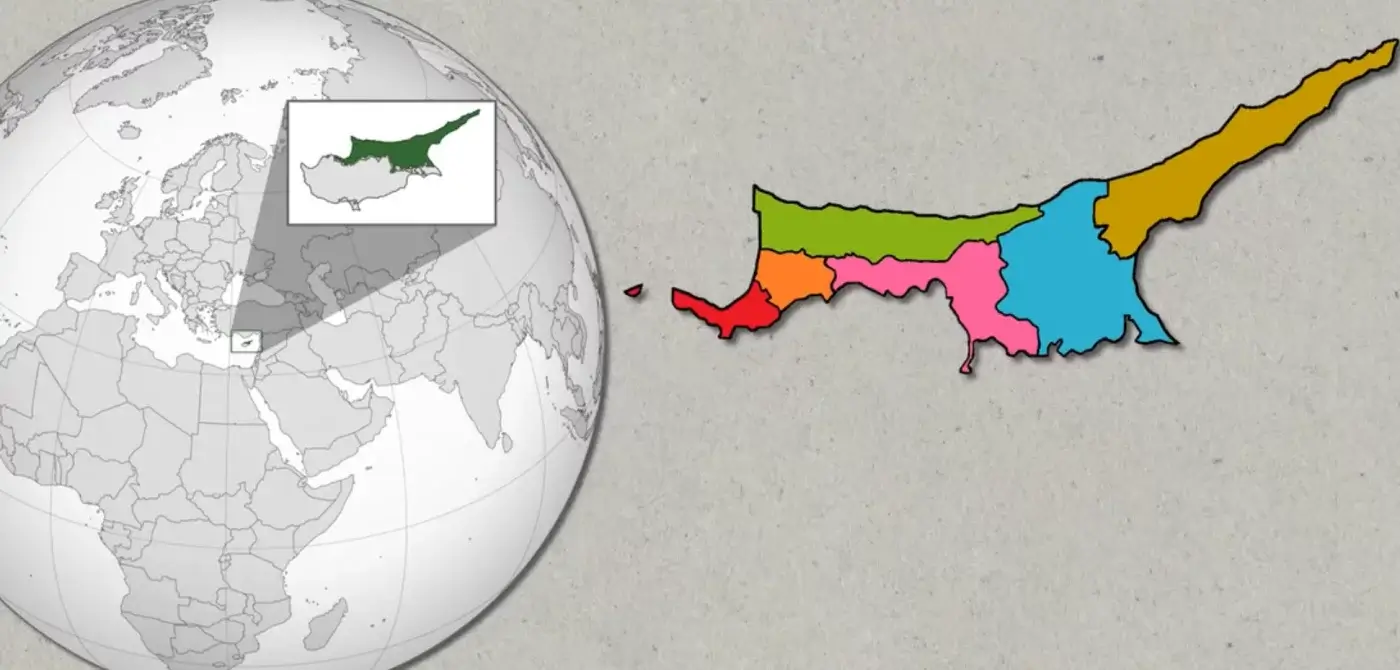

Cyprus is an island in the Mediterranean Sea, with an area of 9,251 square kilometers and a population of over 1.35 million. The distance from Cyprus to Turkey is only 60 km, while to Greece it is 783 km — meaning Cyprus is 13 times closer to Turkey.

Since 1571, Cyprus was part of the Ottoman Empire. Greeks and Turks lived together on the island. After the Ottomans, Cyprus came under British control. By 1960, Cyprus gained independence from Britain. To understand how this independent country later became divided, one must look at the events in Greece.

In 1945, World War II ended, and a Cold War began between the U.S. and the USSR. From 1946 to 1949, a civil war broke out in Greece due to a communist uprising. With the support of the U.S. and Britain, the government prevailed. In 1967, the Greek military staged a coup. The “Black Colonels” launched harsh crackdowns against communists, socialists, liberals, intellectuals, and activists. Human rights were violated to such an extent that Denmark, Sweden, and Norway proposed expelling Greece from the Council of Europe. Before that happened, Greece voluntarily withdrew.

One of the junta leaders, Georgios Papadopoulos, held the offices of Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Interior, and Defense simultaneously. Other military officers also seized key government positions.

In November 1973, mass student protests overthrew Papadopoulos, who was then placed under house arrest. Another military man, Brigadier General Dimitrios Ioannidis, came to power.

During these years, the U.S. was primarily focused on preventing Soviet influence from spreading into Greece. For that reason, Washington turned a blind eye to the repression and even continued supporting Athens during the junta. But after the October 1973 Arab–Israeli War, Saudi Arabia’s King Faisal imposed an oil embargo on the U.S. and its allies. The embargo brought the U.S. economy to a crisis point, limiting Washington's ability to support Greece.

Against this backdrop, to distract the public, Ioannidis launched a campaign under the slogan “Greater Greece,” and on July 15, 1974, staged a coup in Cyprus. Greek troops and armed Greek-Cypriot factions overthrew President Makarios III. After that, repressions against the Turkish population in Northern Cyprus began. Naturally, Turkey could not remain idle. On July 20, Turkey entered Cyprus to protect the Turkish population.

Thus, the state attempting to annex Cyprus was Greece, not Turkey. Turkey justified its military intervention under the guarantor responsibility it obtained in 1960, when Cyprus declared independence under the guarantee of Britain, Greece, and Turkey.

Following Turkey’s intervention, Greece was defeated, and the ousted president Makarios III returned to power. Nine days after the coup in Cyprus, on July 24, 1974, the military junta in Greece collapsed, and the country began transitioning from dictatorship to democracy.

By 1975, the Greek and Turkish communities of Cyprus signed an agreement: the island was to become a federal republic, and repressions against Turkish Cypriots would be prohibited. But the agreement remained unimplemented, and after waiting eight years, in 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) declared independence.

To this day, the TRNC has not been recognized by the United Nations, because the permanent members of the UN Security Council — the U.S., U.K., France, Russia, and China — are not particularly friendly toward Turkey or Muslim countries in general.

Turkey is the only country that has recognized the TRNC. The republic has an embassy in Ankara and holds observer status in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the Organization of Turkic States. However, Western countries — especially the European Union — oppose recognition of Northern Cyprus. Historical resentment toward the Ottoman Empire still influences attitudes toward Turkey. For example, Turkey has been attempting to join the EU for over 40 years. In contrast, Cyprus became a full EU member in 2004 and adopted the euro in 2008.

Do UN Resolutions 541 and 550 remain fully in effect?

According to international law experts — not exactly. There are nuances. On April 24, 2004, a UN-sponsored referendum was held across the island under the Annan Plan proposed by then-Secretary-General Kofi Annan. The plan envisioned a united Cyprus governed by a six-member presidential council: four Greeks and two Turks, who would rotate through the posts of Prime Minister, President, and Vice President. Turkish territory on the island would shrink from 37% to 28%.

So what were the results? 75% of Greek Cypriots voted against unification, while 65% of Turkish Cypriots voted in favor. Why did the Greeks reject it? Because southern Cyprus, inhabited by Greeks, is wealthy, tourist-friendly, and internationally integrated, while northern Cyprus, inhabited by Turks, is under sanctions and economically weaker. Some Greek Cypriots opposed “carrying the burden of the poor north,” using “immigrant Turks from Turkey” as a pretext.

Turkey’s stance regarding the Turkish Cypriots and Northern Cyprus is clear: cultural autonomy and no repression. The TRNC faces two possible paths: either the world recognizes its independence, or it reunifies with the south with full rights and autonomy. Both options secure the rights of Turkish Cypriots.

Northern Cyprus — an inseparable part of the Turkic world

The Turkic world is above all a matter of spiritual, cultural, and national identity. Regardless of where Turkic peoples have historically lived, they are part of the Turkic family. Thus, Northern Cyprus is not a matter of status, but a matter of formalizing an existing identity.

The Turkic world has always faced pressure from global power centers. This will continue. Therefore, Turkic states must simultaneously strengthen territorial integrity and deepen cooperation with other Turkic communities, despite ongoing and future challenges.

Some Turkish media claim that “Central Asia betrayed Turkic unity” and that “Erdoğan lost in foreign policy.” However, political pluralism is strong in Turkey — there are many opposition parties. Those sounding the alarm over Northern Cyprus are mostly opposition media, activists, and thinkers. Official Ankara has remained silent, because the Turkish government believes unity and cooperation should be prioritized over internal discord.

Northern Cyprus is a historical part of the Turkic world, and formalizing its status reflects the importance of development, unity, and collective strength.

Kamoliddin Rabbimov,

political analyst

Read “Zamin” on Telegram! political analyst

Ctrl

Enter

Found a mistake?

Select the phrase and press Ctrl+Enter